Diagnosis and Management of PPID

By Dr. Jaini Clougher, President, ECIR Group Inc.

Equine Cushing’s Disease, more correctly called Pars Pituitary Intermedia Dysfunction (PPID), is a non-cancerous but progressive enlargement of the pituitary gland in the horse. It is estimated that 20 percent of horses over the age of 15 will develop PPID. Note that Cushing’s Syndrome in humans and dogs (when not due to giving too much steroidal medication) involves an actual tumour of either the pituitary or the adrenal glands, (either benign or malignant), whereas Cushing’s Disease in horses has a different cause. Cushing’s Syndrome in humans was first described in 1912 by the American neurosurgeon Dr. Harvey Cushing, who termed it “polyglandular disease.” The combination of an enlarged pituitary gland in horses, along with clinical signs such as polyuria/polydipsia, was first described by German veterinary researcher and pathologist Dr. Georg Pallaske in 1933.

The initial cause of the cascade of events that result in PPID is the loss of dopaminergic nerve cells (neurons that release dopamine) in the hypothalamus. These neurons are key in regulating the conversion of hormone precursors into hormones. When the dopaminergic neurons are lost or become nonfunctional, the pars intermedia of the horse madly produces hormones in an uncontrolled fashion, increasing in size as it pumps out more and more hormones. Key among these hormones is adrenocorticotropic hormone, or ACTH.

ACTH targets the adrenal cortex, signaling it to produce more and more cortisol. Cortisol is an important hormone involved in all kinds of very necessary physiological responses, but unregulated and excessive amounts of cortisol can cause quite a lot of abnormalities. These include suppression of the immune system, loss of muscle mass, thinning of the skin, abnormalities of other connective tissue resulting in tendon and ligament breakdown, increased urination and drinking, and insulin resistance (IR) in horses that are not normally IR or EMS (equine metabolic syndrome).

PPID horses also show abnormalities in heat regulation, with abnormal sweating patterns; poor resistance to parasites (a result of immune system depression); and abnormal hair coats, with long, curly, and non-shedding coats (this occurs later in the progression of PPID, and is not related to excess cortisol, but rather to abnormalities in prolactin production and/or changes in sensitivity to it). Because the dopaminergic neurons in the hypothalamus are also involved in controlling the production of prolactin, PPID mares may lactate without being pregnant or having a foal at foot.

The most devastating clinical sign of Cushing’s disease in the equine is laminitis, which can occur far in advance of any of the other signs. In fact, often the very first sign of PPID is unexplained autumn laminitis.

Related: Laminitis in Horses with EMS and Cushing's Disorder

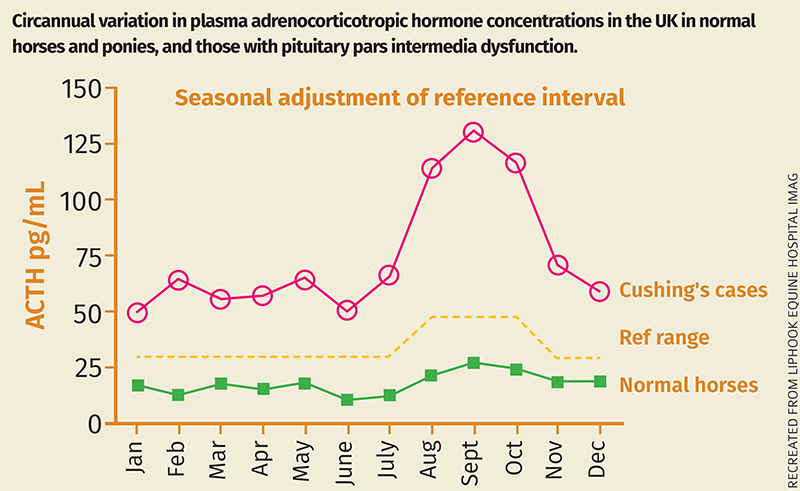

ACTH and the Seasonal Rise

All horses – and, in fact, most mammals that have been studied thus far – show seasonal variation in the production of ACTH and other hormones, controlled by day length. As the days grow shorter, species that have evolved in temperate regions show an increase in ACTH and a decrease in prolactin, which helps prepare for winter: A winter coat is produced, and the metabolism alters so that more fat is stored, which usually involves an increase in insulin. This increase in ACTH is essential for animals preparing for a long, cold winter. In the northern hemisphere (with some variations due to latitude), ACTH starts to increase in late August, and is on the downswing by mid-October. This is known as the “seasonal rise.” PPID horses have a greatly exaggerated seasonal rise that tends to start earlier and last longer. Early cases of PPID will only have abnormally high ACTH during the seasonal rise period, and will have normal ACTH at other times of the year, making diagnosis somewhat elusive. However, as the condition progresses, ACTH will be abnormally high at all times of the year. There will always be a grey area during the seasonal rise in which it is not possible to determine if the horse is truly PPID; a very, very early case of PPID; or not PPID but with a transiently high ACTH.

The abnormal coat of the PPID horse is long, curly, and non-shedding. Photo: Dreamstime/Nicole Ciscato

Diagnosis of PPID

Diagnosis of PPID is by blood tests (endogenous ACTH, plus insulin, glucose, and maybe leptin). Having said that, I will say that if a horse has a long, curly, non-shedding hair coat, loss of muscle mass, weight loss overall, and laminitis, which is worst from September to March, then it is reasonable to assume PPID and start treatment with pergolide, and then get blood tests done as soon as possible. However, it is better to run routine ACTH tests in September once a horse is over 15 years of age to be sure to catch PPID before autumn laminitis turns out to be the first sign that all is not well. This can coincide with the autumn dentistry visit (blood should be pulled before sedation). Note that the TRH stimulation test is not available in Canada.

Related: Feeding Horses with Special Nutritional Needs

Heavy exercise and trailering can cause an increase in ACTH that lasts 24 to 48 hours, so avoid trailering the horse to get the blood pulled, and always wait a couple of days after heavy exercise. Severe pain can also cause a temporary increase in ACTH, so if the horse is suffering from acute laminitis or any other painful condition, it is best to wait a couple of weeks for that to subside. Dormosedan, commonly used for sedation, can cause an increase in glucose, and a decrease in ACTH and insulin, so it is best to collect blood before sedation.

Blood is pulled into an EDTA (purple-topped) tube; a few serum-separator tubes of blood should be obtained as well, as serum will be needed to test for insulin, glucose, and possibly leptin. The blood is spun and separated as soon as possible (within two hours); then the plasma should be frozen and sent on ice. I always freeze the serum collected for the insulin, glucose, and leptin as well, although it is not strictly necessary. It just makes life easier to have all the samples in the freezer, and then if there is any delay in sending the blood, it is preserved until it can be sent.

Why Leptin?

In Canada, asking for leptin to be assayed adds a layer of cost and difficulty, because the only laboratory in North America that currently analyzes leptin is the Animal Health Diagnostic Laboratory at Cornell University in New York. The Guelph University Animal Health Lab will send the samples on to Cornell, but so far Idexx (which many of us use) does not offer this. In Canada, Idexx sends the ACTH out to the Guelph University lab; in the United States, Idexx uses a variety of laboratories. The one reason that a leptin analysis can be useful is that it can help distinguish between high insulin due to baseline insulin resistance, and high insulin that is driven by uncontrolled PPID. It also gives you an idea of the degree of leptin resistance that may be occurring in your horse. However, it is not essential to know this. It may well be more economical to do several insulin, glucose, and ACTH samples to see how things are changing as the ACTH comes under control, rather than do single ACTH, insulin, glucose, and leptin tests. Further, if you have a non-IR prone breed, such as a Thoroughbred, Standardbred, or draft, then it is reasonable to assume that any hyperinsulinemia is driven by the PPID. If you have an IR-prone breed, then it is safest to assume that you have to implement the IR diet as well as to treat for PPID.

PPID horses have an exaggerated “seasonal rise” in ACTH in autumn that starts earlier and lasts longer. In early stages of PPID the abnormally high ACTH will only occur from late August to mid-October, when all horses will have an increase in ACTH and a decrease in prolactin, which helps them prepare for winter. Photo: Shutterstock/Katarzyna Mazurowska

Management of PPID

PPID is a progressive disease; it is never “cured” but can certainly be managed to provide many, many years of quality life. This may well include even FEI competitive life, as the FEI is reviewing its prohibition of pergolide use during competition. PPID horses can certainly continue to compete in non-FEI events.

Horses with PPID should follow the same dietary recommendations as horses with EMS/IR, unless or until blood tests show that the horse is not EMS/IR (see Equine Metabolic Syndrome & Equine Cushing’s Disease in the Early Summer 2018 issue of CHJ). The gold standard for managing PPID is the drug pergolide (marketed in Canada by Boehringer-Ingelheim as Prascend®, and available as compounded pergolide mesylate from a variety of compounding pharmacies).

Pergolide attaches to dopamine receptors in the pituitary gland, mimicking the action of dopamine. However, because the dopamine-producing neurons in the hypothalamus will continue to be lost, the dose of pergolide will need to be increased over time.

Pergolide doses can range from the standard 1 mg to as high as 30 mg or more per horse or pony. It is not dosed to body weight, as most drugs such as antibiotics or anti-inflammatories are; it is dosed to the effect on the receptors in the pituitary. Dr. Eleanor Kellon, co-founder of the Equine Cushing’s and Insulin Resistance Group, states: “The correct dose of pergolide is the one that controls the ACTH.”

Jack with uncontrolled PPID and controlled PPID. Photos: ECIR Group Inc.

My gelding, Merlin, was taking 25 mgs daily; Maggie is currently on 14 mg daily; and Gypsy is on 5 mg daily and has been well controlled on that dose for several years. Other horses or ponies have successfully maintained on doses of from 1 to 3 mg of pergolide for years at a time before having to increase. The Equine Cushing’s and Insulin Resistance Group has been maintaining a Pergolide Dosage Database for many years now; currently, it shows that 48 percent of equines on pergolide take more than 3.5 mg of pergolide daily.

Like any drug, pergolide can have undesirable side effects, especially when starting the drug or increasing the dosage. The most common side effect is called the “pergolide veil,” a transient condition of lethargy, spaciness, and reduced appetite. This can usually be avoided by tapering the dose of pergolide by starting at 0.25 mg and increasing by 0.25 mg every four days, until you reach the initial target dose of 1 mg. The use of the adaptogen APF from Auburn Laboratories has been shown to effectively reduce or prevent pergolide side effects when starting or increasing doses. Use the APF from the day before until a couple of days after reaching the target dose. In Canada, APF is available from Gift Horse Gallery.

To determine if the ACTH is controlled, pull blood to check ACTH levels three to four weeks after reaching the target dose.

Fari, with controlled PPID. Photo: Sarah Braithwaite, Forageplus.

A reasonable alternative to sequential blood testing (although clearly not as accurate) is to monitor physical signs. In order to do this, get a journal and be sure to write everything down, as one’s memory is never reliable past a day or two. Assign each physical sign a number from 1 to 10. The things to look at are fat deposits (especially above the eyes); crestiness of the neck; hardness or firmness of the crest; discharge from eyes (goopy eyes); weight; muscle (topline mostly); comfort on firm ground; amount of urination; water intake; general demeanor; and appetite. Assess these signs every seven to ten days. If you find that there is weight loss with no dietary changes, or the eyes are becoming goopy, the crest is hardening, the feet are getting sore, then it is reasonable to ask your vet for an increase in pergolide dosage.

If you can only test your horse’s ACTH once yearly, then test in August to be sure the ACTH is controlled before the start of the seasonal rise. It is not good enough for the ACTH to be in the high-normal range in August and September, as it will continue to rise over the next few months. Therefore, if ACTH is above the middle of the range at this time, ask your vet for an increase in pergolide. Some PPID horses will start the seasonal rise even earlier; with these horses, test in July.

Thirty years ago, the diagnosis of PPID in a horse was a virtual death sentence, with most horses being euthanized due to recurring laminitis or infections that would not come under control. Advances in knowledge concerning this condition now allow well-managed PPID horses to live full lives.

Related: Spring Horse Health Checkup

Main photo: Dreamstime/Nicole Ciscato