There’s Far More To It Than You Might Think

By Kevan Garecki

My wife and I recently spent four devastating days in Sumas Prairie, Abbotsford, British Columbia assisting with the rescue and evacuation of animals following the disastrous flooding caused by the “atmospheric river” of torrential rain in mid-November 2021. It’s one thing to watch it on the news — it’s surreal to be on the ground in the middle of it.

After five decades in commercial transport, I’ve learned a few things. Anyone with that much successful experience is obligated to share some of it. In light of recent events and on achieving certification in Emergency Preparedness, I’d like to focus on what to and what not to do when things go from bad to downright dangerous.

Looking south on Cole Rd, southern end of the Sumas Prairie, Abbotsford, BC on November 17, 2021. We were trying to get back out of the flats and discovered the road and bridges collapsing right in front of us. Photo: Lexi Jones

It’s important to understand that when we’re loading our horses into the trailer to go for a trail ride, we are relatively relaxed, with time to think about what we’re doing. If something goes sideways it’s seldom a life-threatening situation. But when an emergency and/or disaster strikes, everything changes. That dead calm, self-loading horse can easily become an emotional train wreck. Our expectations of our horses become irrelevant, and even well-practiced routines can go very wrong very quickly. We’ve heard the saying Be prepared to be unprepared inasmuch as our horses are concerned, which is supposed to mean to keep an open mind and realize that not everything is going to fit into neat little boxes. I lean towards a slightly different perspective. I don’t believe in “training” a couple thousand pounds of flight animal that could kill me in a heartbeat; I’d rather prove to him that I can be trusted to make decisions that will benefit both of us. That way he looks to me for guidance. There is absolutely no point in training a horse with fear-based tactics because it’s just a matter of time before he encounters something he’s even more afraid of than you. It’s also not possible to expose a horse to every scary thing in the world, so the trust approach can mean the difference between saving that horse’s life in an emergency, having to leave him behind, or putting ourselves in jeopardy while we waste precious time.

Related: Horse Trailer Accidents on the Road

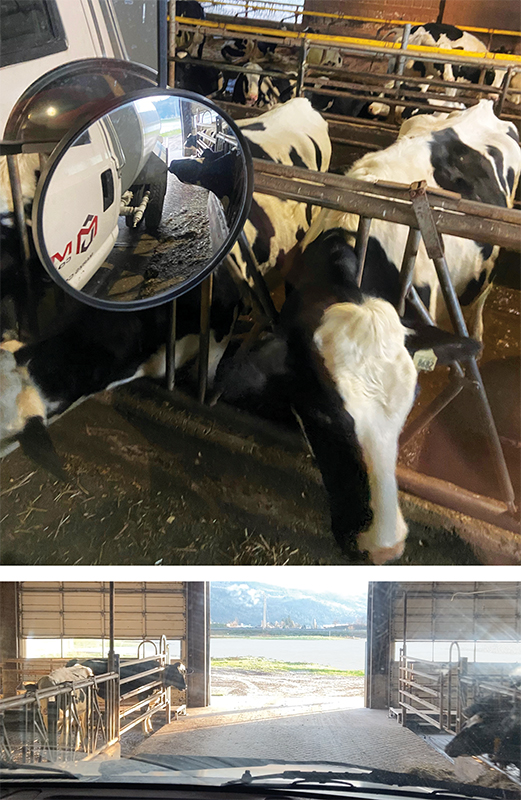

Above (photos)/Below (video): Delivering water to one of the dairies in the Sumas Prairie, Abbotsford, BC. This particular barn had been without water for over 24 hours. Note the cow licking at the truck as we drove past her. By the time we reached out to this farmer, he had his rifle loaded and was about to begin euthanizing his cows rather than watch them die of thirst. Ever have a six-and-a-half foot, 250-pound dairy farmer hug you and burst into tears? It’ll change ya… forever. Photos: Lexi Jones

I’ve lost count of how many evacuations I’ve responded to for which the owners and animals were wholly unprepared. This wastes the responder’s time, because we now have to compensate for panicked animals and hysterical owners while trying to do the job we came to do. The time lost in these situations not only puts us at increased risk, but it erodes the time we need to get to the next place. That half hour I spend loading your horse is 30 minutes I won’t have to save the next one.

Emergency preparedness is not just getting ready for forest fires and floods. It starts with ensuring that our own environments are as safe as they can possibly be. This reduces risks to our horses, which translates to fewer emergency calls to the vet clinic. In the years I’ve been transporting, I’ve responded to an alarming number of cases that were caused by poor management of the horse’s environment. In training and teaching, there’s no such thing as a bad horse, and that horse is never wrong. If you got something you didn’t like or expect, it was your fault — you either didn’t ask the right question, or you asked the question the wrong way. Same principle goes for managing the horse’s environment. It’s not up to the horse to prevent his own injuries; it’s up to us to provide the safest place possible for him to live in. One of my favourite quotes of all time is You become responsible, forever, for what you have tamed by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry in his book, The Little Prince. That responsibility goes far deeper than some folks might consider. Now, let’s take a look at what we can do better!

This was July 13, 2013, driving southbound on the Fountain Valley Road near Lillooet, BC — my “holy s**t” moment — as the wind suddenly changed and swept the fire past me and across the only road I had to get out of there. Thanks to a quick-thinking bomber pilot, this had a happy ending. I never managed to get all the fire retardant off of that truck afterwards, and I was completely okay about that. Photo: Imagery by ManeFrame

Start With a Risk Assessment

Safety begins with our perception of potential threats, and we all know as we gain years around horses that there’s always some unheard-of risk waiting right around the corner. This statement is meant to help you look at your horse’s environment with new eyes. Inspect the barn, hay storage, feed rooms, trailers, and the rest of the property. Some of the most common deficits I see around horse properties are:

- No emergency plans for evacuation or disaster. An emergency response plan should be carefully thought out, include input from your local fire department, practiced regularly, displayed prominently at every entrance to the barn, and revised withany dynamic changes such as new horses, new boarders, changes to the property, etc.

- No fire extinguishers, or those in place are inadequate, dysfunctional, or outdated. There should be a minimum five-pound ABC fire extinguisher at every entrance, and in every mechanical and feed room, and they should be checked at least once a year. EVERYONE should be fully conversant in how to use a fire extinguisher. Teach the PASS System for fire extinguisher use (Pull the pin, Aim at the base of the fire, Squeeze the trigger, Sweep the extinguisher from side to side to blanket the base of the fire in retardant). Test staff, clients, and students annually on fire extinguisher use.

- Poor or improper electrical appliances in use. Fans are often used to help keep our horses cooler in the summer, but household fans are not designed for use in barns. The motors in household units are not sealed and in time they can become clogged with highly flammable dust, quite literally making them time bombs for fire. Fans used in barns must be designed for agricultural use. I also see household extension cords used all over barns; not only do these have insufficient insulation to prevent accidental cracking and exposure to live electricity, but the wires in those cords are often rated far too low for some of the things typically plugged into them in barns (fridges, kettles, shop vacuums). Electrical extension cords used in barns should be rated for outdoor use and for the appliances they are being used for.

- Buildup of dust, debris, cobwebs, and other material that can either cause or increase the severity of a fire. Dust is extremely flammable, and when it accumulates on spider webs it can literally turn into a blanket of flame that can spread with alarming speed. Debris such as hay, bedding, and feed often collects in corners or around the edges of stalls and rooms. These pesky little pockets of material can become instant hot spots that accelerate a fire.

- Poorly designed and/or non-functional entrances. This is a biggie with me because if I need to get a horse in or out even in calm conditions I don’t want to be fighting with a recalcitrant gate or door. In an emergency, wrestling with one of those can mean the difference between getting a horse to safety or not.

Related: Equine Insurance Coverage for Natural Disasters

If this horse could talk, he’d remind us to always perform regular pre-trip trailer inspections before loading up and taking your rig out on the road. Photo: Imagery by ManeFrame

Cast a wary eye across your property as well:

- Check all gates for proper operation. Do they hang precariously? Are the hinges mounted in a way that prevents accidental or intentional removal of the gate? Are latches easy to use, or could they become a panic problem?

- Fencing should be checked weekly at a minimum. I think there are little gremlins who live specifically in fencing materials and venture out very late at night to sabotage even our most carefully attended sections. We have virtually bulletproof high density polyethylene fencing, and last week one of our horses figured out how to dismantle it.

- Is your driveway clear and well-maintained? I’ve been to places that took several extra minutes to get into and out of in the trailer because the driveway was strewn with leaves, potholes, and runoff rivulets, and branches and other materials were overhanging the regularly-driven portion. Those are precious minutes the vet just might need to save your horse in the event of illness or injury. Even a moderate coating of leaves can turn a driveway into a skating rink in the rain.

Many of these same subjects can apply to our trailers as well, as those considerations are very similar:

- Have an action plan in the event of a flat tire, breakdown, bad weather, or other unexpected delay. Keep weather-consistent clothing on board, along with extra hay and water for the animals, and drinks and snacks for the people.

- EVERY rig that hauls horses should have TWO minimum five pound ABC fire extinguishers — one in the trailer and one in the truck. Both should be easily accessible and checked twice a year for compromises (twice a year because they typically endure far more abuse than one just watching you from the barn doorway). Mine are attached to the front of the trailer in a weather-resistant cover, and in the cab mounted just inside the driver’s door.

- Perform regular inspections, pre-trip walk-arounds and tire checks, and ALWAYS do a four-way brake test before rolling. Those five minutes before placing the rig into service for the day have prevented numerous delays for me. I’d far rather fix something in the comfort of my own driveway than out on the side of the road.

- Be fanatical about cleaning because manure, urine, road chemicals, etc. can make short work of floors, walls, and even welds and other structural components.

- The only thing I’m even pickier about than cleanliness is maintenance; there’s no such thing as any part of a truck or trailer that works too well. If it needs attention, get it fixed before you roll.

Above (photos)/Below (videos): Driving along a flooded road in Sumas Prairie, Abbotsford, BC in mid-November, 2021, between the utility poles which indicate where the road is/was. We were assisting with the rescue and evacuation of animals in this farming community. The devastation was utterly soul shattering, despite the fact that because this is almost exclusively a farming community the residents were a little better prepared than most. Photos: Lexi Jones

Your Emergency Preparedness Plan

This is just a sampling of what must be scrutinized during a comprehensive risk assessment and incorporated into a subsequent emergency preparedness plan. As mentioned above, every emergency plan should include input from your fire department. Most fire departments will visit your farm if invited, and make note of the following when they do a site visit:

- Ingress and egress;

- Whether they will need to wait for access, such as with an electric gate — and the contingency plan if the power is out;

- Topography;

- Unmanageable risks such as waterways crossing or bordering the property, or steep hills that could fail in an erosion or flood situation;

- Manageable risks such as those pointed out in the barn and property surveys;

- Nearest access for water, muster points for people and animals, where they can park and set up their equipment, etc.

Some fire departments will file your emergency plan under your address, so they can pull it up at a moment’s notice and be prepared for what they’re racing into. Keep in mind that if you ever have to call the fire department for help, they don’t come thundering down the driveway the second you hang up the phone. It takes time to dispatch the call, get the crew into the truck(s), get on-site, and set up everything that might be needed. In our farm assessment, it was estimated to take 18 minutes from the time of a 9-1-1 call until actual engagement of fire crews and equipment. Our place is less than two miles from the nearest fire hall and it would take them nearly 20 minutes to begin saving us, and that’s under ideal conditions. It’s a sobering thought, and one that should solidly drive home just how critical a sound preparedness plan really is.

Your pre-plan should map out the location of all emergency utility shut-offs and identify all buildings and sources of water available should firefighters require access to it. It will also include the locations where all animals are housed. The plan should be stored in a neutral location on site, such as on the side of the house or a drive shed, or in a lock box at the gate that emergency responders have access to.

Related: Wildfire, Flood, Earthquake! Horse-Specific Emergency Planning

This was July 28, 2021, near Petit Creek wildfire, west of Merritt, BC. The main roads had already been closed with us still inside… and we were trying to find another way out. Photo: Lexi Jones

Regional Disaster Plan

All of the foregoing focuses on preparing for what we would define as a “personal” event — fire or accident at the barn, sick or injured horse, or some other situation that involves your property exclusively. But what about regional emergencies such as wildfires, area floods, and earthquakes? Large-scale disasters can be particularly daunting because it’s not just a matter of help getting to you. There are typically hundreds or thousands of others affected as well, and emergency responders may be forced to triage based on risk levels, access, severity of exposure to danger, and numerous other factors. This once again should highlight the need for a comprehensive plan in the event of a regional disaster. Fire, flood, and earthquake plans are largely similar, with only a few incident-specific anomalies:

- Plan how you will get your horses out, and where you will go. Who will you call first? What’s your contingency if you lose contact with any of your family members?

- Have you packed an emergency kit of food, water, clothing, and other necessities? Bug-out bags are pre-prepared survival kits that allow you to evacuate quickly in the event of disaster. A rule of thumb for packing bug-out bags is they should be sufficient for at least a week for every person and animal you’re responsible for.

- Do you have first aid kits and at least rudimentary knowledge of how to use them?

- Do you know how to access regional, provincial, and federal emergency announcements? Even simple things like keeping an eye on severe weather can make a huge difference.

- If you are ever faced with an evacuation alert, GET OUT — RIGHT NOW. DO NOT WAIT for an alert to become an order. Often the orders come with literally minutes to react, and it’s just never enough time. All of the rescues and responses I’ve done over the years have been the result of people not being willing or able to get out in time.

In the recent massive flooding in the Sumas Prairie, I began with animal transport and found that many farmers had already moved some of their herds to safety before the rains became biblical in proportion. The unexpected element was the water main rupturing, leaving thousands of people and animals without drinking water. We responded to that development by using a water tanker donated by Marex Constructors Ltd. of Abbotsford and spent three harrowing days hauling water into the area for those herds and farmers still stranded. There was an interesting denominator in that event; being almost exclusively a farming community, folks were just a little better prepared than most, but even so the devastation was utterly soul shattering. Thousands of animals perished, families will need years to recover from the tragedy, and some properties literally vanished from existence. Those folks did pretty much everything right and they still barely made it.

I’d like to offer some perspective from many years of disaster and emergency response. I’ve participated in fire evacuation, flood response, assisted with countless SPCA issues, and much more. Here are a few of the things I’ve learned:

- No matter what you think you know, it’s not enough.

- If you have everything you could possibly need on hand, you’ll either need twice as much as you have, or you’ll need something no one has thought of yet.

- If you have three responders on site, you’ll need eight. If you have eight, you’ll need 20.

- When the assessment forecast looks like a six on a scale of 10 in severity, it’ll hit 15 when you glance the other way.

- Murphy’s Law states that anything that can go wrong, will go wrong, and will do so at the worst possible juncture.

- Murphy was an optimist.

See more videos of the BC Flooding 2022 by Lexi Jones here.

Related: Equine Emergency Preplan Checklist

To read more by Kevan Garecki on this site, click here.

Main Photo: Dreamstime/Fedor Lashkov