Stomach Bots and Tapeworms

By Margaret Evans

As the season moves toward early fall, your parasite management program should give some attention to stomach bots and tapeworms. To control these parasites more effectively, it helps to understand their life cycles.

Stomach Bots

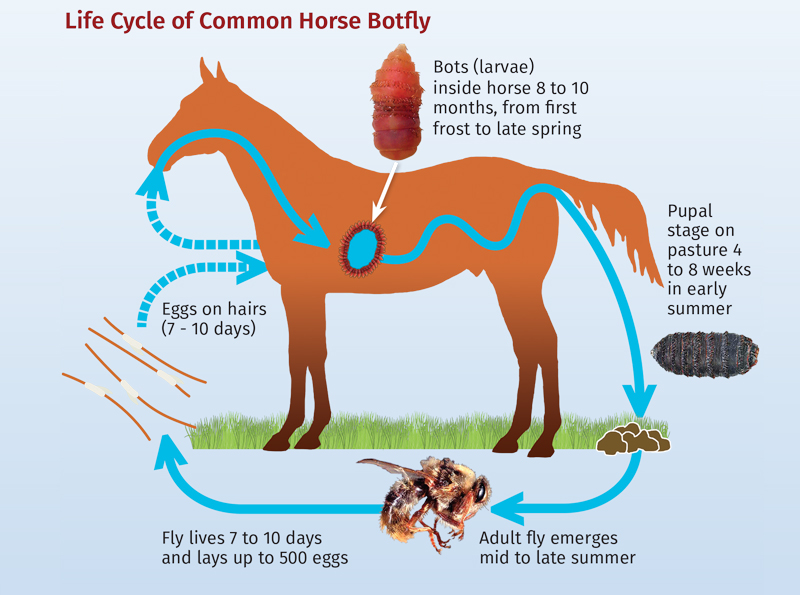

Bot flies are honeybee-sized flies that attach their tiny yellow, orange, or cream-coloured eggs to the horse’s hair coat during summer and fall. The eggs are readily visible on most horses, especially those with dark coats. The larvae are triggered to hatch when the horse self-grooms or licks the site, generating warmth. The flies themselves are not a particular nuisance to horses; it is the ingestion of the larvae and their accumulation in the intestine that may create infestation problems.

According to Dr. Wendy Pearson, Ph.D. (Dr. of Veterinary Toxicology) with the University of Guelph, North America has three primary species of bot fly and they are identified by where they lay their eggs on the horse. The common bot fly lays eggs on the shoulders and front legs. The throat bot deposits yellowish-white eggs on the hairs growing in the space between the jawbones, and the nose bot lays black eggs on the tiny hairs adjoining the lips.

All three of these bot species hatch outside the horse, and the emerging larvae find their way into the horse’s mouth where they burrow into the gums around the teeth for several weeks until, in their second stage, the larvae are swallowed and attach themselves to the stomach lining. The final-stage larvae move into the small intestine and attach themselves to the lining where they stay until spring and shed out through the feces. Treating horses for bots in the fall will help control the springtime shed and reduce the numbers of adult flies. A severe infestation of bot larvae can cause ulcers around the mouth or in the stomach, and large numbers of larvae may cause blockage leading to poor appetite, abdominal pain, and colic.

Once outside the horse, the larvae pupate and the mature fly emerges in four to six weeks. It mates, lays its eggs on horse hair, and the cycle begins all over again.

Combating bots can be done to some degree by washing off the eggs with warm water, which will cause the eggs to hatch and they will die before they enter the horse’s mouth. Clipping the hair or scraping the hair with a bot knife is also effective. But it is unlikely that all the eggs will be caught. The most effective way is to treat the horse with an ivermectin product recommended by your vet.

Practicing environmental hygiene is an effective way to reduce the risk of parasite infestation. For regular cleaning of the pasture and turnout paddock the shovel and wheelbarrow is effective but decidedly low tech and time consuming. If you have larger pastures and several horses you might want to invest in a machine towed by your tractor, ride-on mower, or a quad that scoops or vacuums up manure, dead leaves, garden debris, small construction materials, and anything that normally requires the wheelbarrow.

Related: Fall Leaves - Are They Toxic to Horses?

Botfly eggs attached to the horse’s hair coat can be removed by clipping the hair, scraping the hair with a bot knife, or washing with warm water which will cause the eggs to hatch and the larvae to die before they enter the horse’s mouth.

Tapeworms

The relationship between grass, mites, the horse, and the tapeworm is also an endless cycle. Tapeworms belong to a group of parasites called flatworms or cestodes. They have a scolex, or head, and a flattened body. The scolex has four suckers, which the tapeworm uses to attach to an organ such as the horse’s intestine. The flattened body, or strobila, has a ribbon of segments called proglottids through which nutrients are absorbed.

There are three species of tapeworm, the most common being the cecal tapeworm. The cycle begins when the tapeworm’s egg is eaten by a grass mite that climbs onto pasture grasses, which are then eaten by horses. The young tapeworm grows and matures inside the horse in about eight weeks and attaches to the lining of the small intestine. Tapeworm eggs are passed in horses’ feces and are in turn eaten by the grass mites rekindling the cycle all over again.

Manure left in paddocks and pastures is the most common source of parasites. Manure removed at least twice per week can reduce your horse’s overall parasite load by more than 80 percent. Photo: Canstock/Pike

Tapeworms are reported in at least 50 percent of grazing horses and were found in 50 percent of Thoroughbreds examined in central Kentucky. Usually, they do not cause clinical disease but their presence still needs management, especially in weanlings and aged horses over 20 years. However, tapeworm infections have been associated with colic, weight loss and horses in poor condition. Management includes deworming based on your vet’s recommendation, and is usually done annually in the fall.

In recent years, there has been concern about internal pests becoming resistant to deworming products. Indiscriminate and frequent use of deworming products can actually increase the rate at which parasites become resistant and the practice may not target the actual pest your horse is harbouring.

Parasites can cause problems in horses depending on their age and health status. But with good environmental hygiene and cautious, veterinary-guided use, deworming may only be required twice a year to keep an adult horse healthy.

Related: Preventing Fall and Winter Colic

Related: 8 Ways to Think Like a Parasite

To read more by Margaret Evans on this site, click here.

Main photo: Shutterstock/ESOlex